Marianne Vitale: Tennis Elbow 104

-

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, Beach, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm)

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, Beach, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm) -

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, Orange, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm)

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, Orange, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm) -

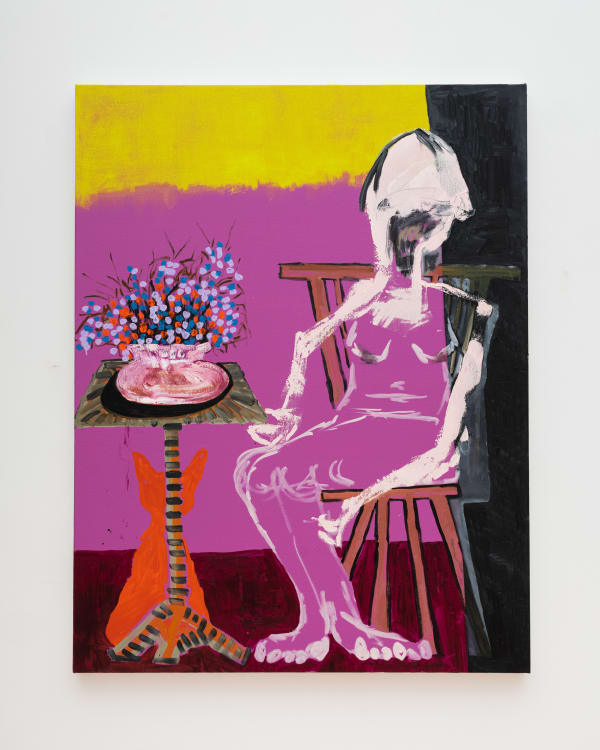

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, Seated, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm)

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, Seated, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm) -

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, with Cat, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm)

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, with Cat, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm) -

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, with Lemons, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm)

Marianne VitaleSelf Portrait, with Lemons, 2022Oil on canvas53 x 41 in (134.6 x 104.1 cm)

#Happy #Horror #Seaside #Tragedy #Lemony #Monster #Sunshine #Destruction #Tranquil #Crash #Sand #Blast #Bridgetonowhere #Apocalyptic #Eden #EternalSummer #NuclearWinter #ChangeNow #MutationNo #Oil #Vinegar #Painting #Sculpting #Cooking #Baking #Breathe #Scream #Coasting #Ghosting #BeachTowels #ScreechOwls

Any guess that anyone makes today is just a stab in the dark.

But someday, someone will look back and scrutinize today’s profoundly strange little window of time—the invisibly creative production of the early 20s—and somehow, they will see something that no one today can. They’ll understand in the greater scheme of things what the desolate panic of quarantine and the ensuing years of forced normalcy did to art, artists and all creative people.

The first artworks chosen for the canon of this genre-to-be (Postviralism? Rococovid?) might well be the five beautiful and disturbing paintings on display at New York’s Journal Gallery by the noted New York sculptor Marianne Vitale. But the fact that they are painterly paintings from a staunch sculptor only hints at what a departure they are from her “normal” work— like her well-known, burnt-black steel bridge models which were shown at the Venice Biennale Arsenale this year.

Colorful, messy, angry, intuitive, hesitant, creepy, rebarbative, peaceful, vengeful, unbalanced, chill, afraid. All the aesthetic emotions that go into what Vitale calls self-portraits, are mixed together about as often as bleach and ammonia. (Don’t try it.) But if the finished paintings are a raw, refreshing kind of a balance of opposites, it was never the plan.

In fact, it was the experience of participating in the world’s most prestigious art exhibition that got Vitale thinking.

“The world is insane now—but what can you do?” Vitale says this one bland thought kept running through her head for the weeks and months while she was preparing her work for Venice. “I have been working on the burned bridges series for over ten years, casting them in a foundry, and all of those works there will last three ice ages. But I call that work dead, and in some ways it really is. And then Venice is also old, and also dying. Everything started to feel so heavy, like a cemetery.”

Add to that the fact that Vitale’s dark-hearted bridges, husks of failed industrial expansion in the U.S., were being shown in what was history’s first military-industrial complex, the Arsenale, and the whole morass of it started to feel grandiose and deathly.

When Vitale got home from Venice in May, she felt she had been through an old black wrought-iron wringer of her own creation. It was time for a change. Or at least an experiment. She wanted to throw everything she knew out the window and start over, from the beginning. From a beginning.

“After Venice, coming home seems like it was like some sort of rebirth,” says Vitale. “I wanted to make art that felt alive.”

As May moved to June, Vitale sequestered herself at her summer house in Massachusetts, dug up some supplies (in this case a cache of oil paints, canvas, mediums and solvents, mostly purloined from her husband, artist Rudolf Stingel) and got to work. Except that she didn’t really get right to work, she found herself at a loss. That was the bad news, but also the good news.

Who knows whether Vitale knew tennis legend Arthur Ashe’s famous advice to anyone bollixed up in a mess—“start where you are, use what you have, do what you can.” Either way, that sensible spirit was basically how Vitale decided to approach this. Her other guiding light was her firm conviction that she would in no way draw upon the rectilinear aesthetics and forged-steel recipes of her sculpture practice.

“When I get my hands on paint, it accesses a different part of my brain,” says Vitale. “It is like a different planet. I’m able to express myself in more vibrant ways somehow. I want to believe that painting is fun. I get to use color—and I just went for the brightest colors, right out of the tube. It was very experimental."

There is no denying that Vitale’s desire to break out of her well-articulated sculpture vocabulary and reach out for color was a success. The canvases in the Journal Gallery show are colorful enough to be beach towels. But Vitale’s canvases aren’t intriguing because of some chipper, childlike embrace of pure pigment. Far from it. Pretty colors may have been where Vitale started out but not where she ended up: with monsters stalking and lounging throughout the parti-colored scenes, nightmares that would give Bacon or Redon pause.

“At first, I was thinking, OK, let's make beautiful paintings,” said Vitale. “And there really was an attempt at trying to make something beautiful. But then, I found myself tapping into how I really feel, so, you know, it’s rage and horror and terror. Yes, here we are at the beach, but this is all very wrong. I am able to express myself in more vibrant ways, but it still taps into the darkness, and it’s still painful to make the art.”

Someday, someone will get exactly what Vitale was on about with these barbaric beauties, hybrids of floating butterflies and murder hornets. We can understand it on a somatic level, we can feel our eyes’ desire for some quiet prettiness but also our guts’ inability to stifle the screams.

You hear people talking about a return to normalcy, and you can’t help but ask—Was it really ever normal in the first place?

Anyone who says they understand today is misguided or mistaken. As Vitale’s work unclearly shows, the only thing to put any faith in is stabs in the dark.

David Colman